Stop Naming Everything `Impl`

Posted on October 13, 2025 • 4 min read • 848 words

Stop Naming Everything ‘Impl’: The Interface Anti-Pattern

Ah, FooImpl. The class name that quietly signals, “I followed best practices…sort of.”

I’ve seen this pattern countless times: an interface with a single class implementing it, the class name ending in

Impl. Developers do it thinking they’re being effective: SOLID, testable, future-proof.

What they’re actually doing is creating unnecessary friction for everyone who comes after them.

“Why come up with a meaningful name when ‘Impl’ works for everything?”

— apparently a popular belief.

In this post, I’ll explain why the Interface + Impl approach is usually overkill, how it leads to messy, bloated code,

and what a healthier, more maintainable alternative looks like.

Why We Fall for It

The motivations are understandable:

- Contracts: “Interfaces enforce the shape of a class.”

- Testing: “Mocking frameworks love interfaces.”

- Architecture points: “I’m following SOLID principles.”

Here’s the catch: creating a single interface for a single class doesn’t really enforce good design. It’s a premature abstraction, solving a problem that doesn’t exist yet. You end up with an extra layer of indirection, no real flexibility, and a class that slowly turns into a God Class.

“We’re preparing for multiple implementations…that will never come.”

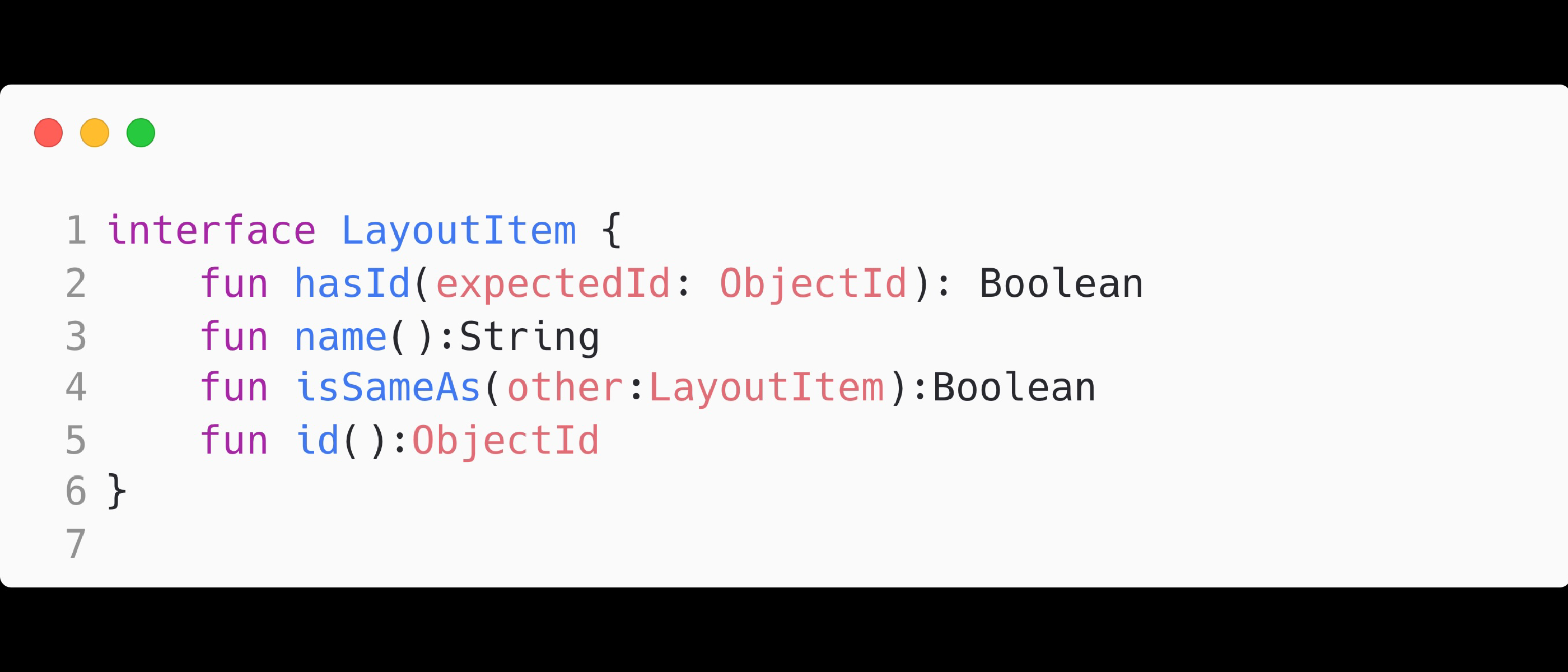

Interfaces Exist to Separate What From How

The purpose of an interface is to define what something does without dictating how it does it. This is particularly

powerful when you have multiple implementations with different strategies — a FileStorage and an S3Storage, or a

CacheRepository backed by Redis versus one backed by Memcached.

This is where the

Interface Segregation

Principle (ISP)

becomes crucial: clients shouldn’t be forced to depend on

methods they don’t use. ISP pushes us to create small, focused interfaces that serve specific needs rather than

monolithic contracts that try to satisfy everyone. When you create a single interface with a single Impl, you’re not

separating “what” from “how”, you’re just duplicating your class definition. You’re definitely not practicing interface

segregation; you’re doing the opposite. You’re coupling your entire class codebase to one bloated contract that will

inevitably grow beyond its original purpose, forcing every client to drag along dependencies on methods they’ll never

call.

God Interface → God Class

One method becomes five, five becomes ten. Suddenly, the interface is doing too much, and the class implementing it is taking on responsibilities it shouldn’t have: persistence, logging, emailing, analytics …maybe even making coffee.

public interface UserService {

void createUser(User user);

void deleteUser(User user);

void updateUser(User user);

List<User> findAllUsers();

void sendWelcomeEmail(User user);

void logUserActivity(User user);

// And the list goes on...

}

public class UserServiceImpl implements UserService {

// Chaos inside

}A common extension of this problem occurs when a new interface is needed. Instead of adding the new interface to the implementing class, developers extend the existing “God Interface,” making it even bigger:

public interface SomeNewService {

void doSomethingElse();

}

public interface UserService extends SomeNewService {

void createUser(User user);

void deleteUser(User user);

void updateUser(User user);

List<User> findAllUsers();

void sendWelcomeEmail(User user);

void logUserActivity(User user);

// And the list goes on...

}This approach compounds the problem: the interface grows uncontrollably, classes become tightly coupled to an ever-expanding contract, and the original separation of concerns is completely lost. The result is bloated, difficult-to-maintain code and a higher risk of bugs whenever the interface changes.

At this point, you’ve created a maintenance nightmare: hard to test, hard to extend, and impossible to reason about.

Cultural Pressure Doesn’t Help

This pattern isn’t just a coding mistake, it’s reinforced by culture:

- Templates & “Best Practices”: Many teams are told, “Always create interfaces,” without context.

- Misunderstood purpose: Interfaces exist to define contracts for multiple implementations, not as a default.

- Premature future-proofing: Planning for flexibility that may never be needed.

“It’s not a bug. It’s corporate policy.”

A Better Approach: Let Abstractions Emerge

Here’s the rule I follow as a Technical Coach: Create interfaces that separate concerns and help better organize our domain around the ‘Why’ of functionality.

- Keep interfaces small. Respect the Single Responsibility Principle.

- Favor composition over inheritance. Break responsibilities into focused collaborators.

- Let the code tell you which abstractions are necessary.

- Lean on YAGNI, XP, and TDD to guide emergent design.

Instead of a monolithic UserServiceImpl doing everything, you could have:

public interface UserRepository { ... }

public interface EmailService { ... }

public interface ActivityLogger { ... }

public interface UserService {

void createUser(User user);

void deleteUser(User user);

void updateUser(User user);

List<User> findAllUsers();

}

public class DatabaseUserService implements UserService {

private final UserRepository repo;

private final EmailService emailService;

private final ActivityLogger logger;

// UserService implementation

}Clean. Testable. Focused. No “Impl” suffix in sight.

Before / After

Before: UserService + UserServiceImpl juggling persistence, logging, and emails.

After: UserService composed of small, meaningful interfaces handling their own concerns.

Separation of concerns is a far better design goal than any

Implsuffix.

Takeaway

Stop creating one interface as a contract for everything the class does. Let abstractions emerge naturally, and use them to separate concerns, not as a preemptive template.

FooImplisn’t clever. It’s a design smell. One that will make life harder for anyone maintaining your code.